In the hubbub surrounding the recent passing of the queen, the word I keep encountering in all kinds of places is duty.

It’s a concept I was already mulling over as I finished the excellent Miss Austen by Gill Hornby. The novel, wreathed in calm shot through with an old loneliness, extrapolates from a famous but mysterious incident in the Austen family—that after Jane’s early death, her sister Cassandra was known to destroy correspondence written by her famous sister.

After all, “Cassandra was the executor of her sister’s estate: the keeper of her flame; the protector of her legacy.” Our protagonist is defined by this sense of obligation. Wearily in old age, Cassandra observes to herself, “A single woman should never outlive her usefulness.” Later, she remarks, “It is as if Nature can only throw up one capable person to support each generation. In my family that has always been me. […] Our fortune is to have families who need us. It is our duty, our pleasure. Our very worth!”

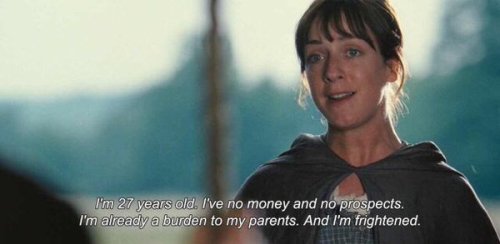

Throughout the novel, then, Hornby works to valorize this humble dedication to duty, illustrating the unflashy devotion Cassandra shows her sister, Jane, and their family, even when it requires self-denial. In this way, Cassandra resembles the quieter heroines her sister dreams up: the Elinors, the Fannys, the Annes. This duty is no pitiful delusion, either, for as Cassandra declares silently, “Look at me, Isabella! I have known happiness. Without man or marriage, I found a happiness, true and sublime!” (And this, the cautious reader should note, is not revealed to be a secret anachronistic fling, either, rest assured.)

Struck by tragedy while still a young woman, Cassy resolves, “From the moment the news had been broken to her—badly, insensitively, not as she would have liked or deserved, but no matter—Cassandra had identified that as the occasion to which she must rise.”

While we can and maybe elsewhere should argue whether the late queen’s duty was one worth always following, even when it pitted her against ex-subjects in the developing world or her own family, certainly we can recognize that in her day to day life, in both its splendor and tedium, Elizabeth unstintingly gave her life to her perceived duty.

And maybe that’s what fascinated so many of us, whether we were avid consumers of royal gossip or simply casual viewers of The Crown: her duty was both like and unlike our own. In her decades of service were jewels and rich brocade, private jets and dignitaries, far from our own sometimes dull-as-dishwater domestic duties. And yet there is something recognizable, something lacking in the lives of so many public figures, who seem committed only to a life of ambition or pleasure. This may be part of Elizabeth’s enduring appeal for many, that, like the costume dramas to which so many of us kinda religious, kinda stay-at-homey ladies find ourselves drawn, in Queen Elizabeth we recognized a woman like ourselves, trying (though sometimes failing) to discern what was right and to do it — rather than just what would make her happy.

We have, of course, the purer, undiluted example of the saints. But for so many of these, the example is often a fierce and alien flame: a blazing martyrdom, a heroic triumph. That’s why we gravitate to the small and attentive dutifulness of figures like St Thérèse of Lisieux, I think, toiling away in their mundane, quiet corners, but find the writ-large duties of the royal materfamilias so fascinating.

Cassandra’s reward for a lifetime of service comes in perusing a last letter of Jane’s, in which Jane deems her the “dearest, tender, watchful sister,” and, with a rare straight-faced earnestness, proclaims, “As to what I owe her, I can only cry over it and pray God to bless her more and yet more.”

It’s all any of us can work for then—a little gratitude, a little recognition, the prayers of those around us, whether we end up as the longest reigning monarch of England or the sister in the shadows. I hope that ultimately Queen Elizabeth found those things for herself—and that I might, too.